Fast and elegant way to sum primes in a gigantic range

1/Jun 2009

The problem is taken from Project-Euler, which asks what is the sum of all prime numbers under 2 million.

Traditional Approach

Project-Euler has many problems like this which looks ridiculously easy in theory, but practically impossible when using the old-school brute force way to solve them.

Even after applying some well-known techniques to shrink the problem space, the computation still takes a long time (too long for me to stick around and wait it to finish). I tried using the sieve of Eratosthenes, and the performance isn’t satisfying to say the least.

solve() ->

sum_all_primes_under(2000000).

sum_all_primes_under(To) ->

sieve(lists:seq(2, To), To).

sieve([], _) -> 0;

sieve(List, Range) ->

[Max|_] = lists:reverse(List),

case Max List;

false ->

[H|Rest] = List,

io:format("~p ~n", [H]),

H + sieve(lists:filter(fun(X)->X rem H =/= 0 end, Rest), Range)

end.

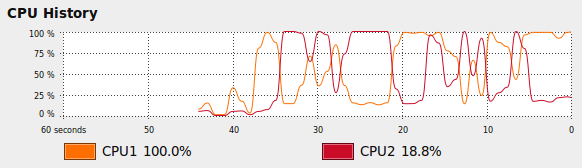

One thing to take note is that when executing the above program, only one core of the CPU is effectively utilized.

CPU chart before

Concurrency Oriented Programming

In the concurrency oriented programming (COP, a term coined by Erlang’s inventor Joe Armstrong) model, you’re thinking in terms of separate entities and what responsibility is there for each of them. Think of them as individual human beings. They don’t have shared brains; one cannot influence the other by simply modify his or her brain tissues (well, under normal circumstance anyway). As human beings, our brains are disconnected from each other, but we share our knowledge through communication. We can modify other people’s memories by sending messages and vice versa. This is essentially what COP is – the entities are processes, and each has individual memories that’s not modifiable by other processes. Processes communicate with each other through message sending/receiving. This model is particularly good for scaling. Because the entities share nothing, it’s easy to get more entities without worrying that they don’t get along.

Back to our problem. With the traditional approach, one process is to iterate through the 2 million numbers, determine if it’s a prime number, and add to the tally if it is. Think of it as one man doing all the job that there is.

With the new model, here are the actors in our system:

Worker: A worker is responsible for gathering the prime numbers in a given range (sufficiently small), add them and report them to the tallier.

Tallier: A tallier waits for the results from the workers and sum the results up.

Manager (Solver): The manager is responsible for dividing up the task, hiring workers to finish the task and tell the tallier which worker has been given a task so that the tallier can wait for the specific workers to send back the results.

worker() ->

receive

{TallierPid, L} ->

Sum = lists:sum(lists:filter(fun(X)->mylib:is_prime(X) end, L)),

TallierPid ! {self(), Sum}

end.

The worker code is quite simple. After it’s created (hired by the manager), it waits for the manager to send over {TallierPid, L}, with L being the list of integers to work with. Then it filters out the prime numbers, and call lists:sum() on the result list, which gives the sum of the prime numbers in the list L.

This doesn’t seem to look different if we were writing in the traditional way. Yes, but feeding the key difference here is that we’re not going to ask one worker to solve the entire problem domain. Instead, the manager is going to divide the task into smaller tasks so that it takes almost no time for a single worker to finish his or her work.

solve() ->

TallierPid = spawn(euler, tallier, [self(), [], 0, false]),

solver(TallierPid, 2, 2000000),

%% worker assignment has finished

TallierPid ! { self(), true },

receive

{TallierPid, Result} ->

io:format("Final tally: ~p ~n", [Result])

end.

This is only half of the manager code. First it spawns a tallier. We’ll look at the tallier code later.

solver(TallierPid, 2, 2000000) is the worker assignment part, which is shown directly after this section.

After the worker assignment, the manager simply informs the tallier that the worker assignment has done, and sits there, waiting for the tallier to report the final result.

solver(TallierPid, From, To) ->

case (To - From) of

SmallRange when SmallRange =< 1000 ->

List = lists:seq(From, To),

WorkerPid = spawn(fun worker/0),

%% register the worker with tallier

TallierPid ! { self(), WorkerPid },

%% send the problem for the worker to work out

WorkerPid ! { TallierPid, List };

_ ->

Mid = mylib:floor((To + From) div 2),

solver(TallierPid, From, Mid),

solver(TallierPid, Mid+1, To)

end.

This code defines the problem domain, splits the work, hire workers and assign the split work to them. It’s a classic divide-and-conquer structure, however, we have to be careful not to make the range too small, as the number of processes may (or in this case, will) exceed the default system limit. As I tested, my computer can sum prime numbers from a list of 1000 elements in a heartbeat so I just chose that number to be the upper bound of the size for each worker to work on.

Finally,

tallier(SolverPid, Workers, X, AssignFinished) ->

receive

{SolverPid, true} ->

%% This message is from the solver

%% It tells the tallier that

%% worker assignment has finished

tallier(SolverPid, Workers, X, true);

{SolverPid, WorkerPid} ->

%% This message is from the solver

%% Register WorkerPid

tallier(SolverPid, [WorkerPid | Workers], X, AssignFinished);

{WorkerPid, Sum} ->

Tally = X + Sum,

%% Remove worker from Workers list

NewWorkerList = Workers -- [WorkerPid],

case AssignFinished of

true ->

case NewWorkerList of

[] ->

SolverPid ! { self(), Tally };

_ -> tallier(SolverPid, NewWorkerList, Tally, AssignFinished)

end;

_ -> tallier(SolverPid, NewWorkerList, Tally, AssignFinished)

end

end.

The tallier keeps track of 4 “variables”:

1. The Solver’s ID – to recognize messages from the solver and to report final tally to the solver.

2. A list of Workers’ IDs whose results have been reported yet.

3. X – The previous tally.

4. AssignFinished – a flag indicating that all workers have been assigned.

The tallier has to look after three types of messages:

1. Message from the manager that the job has been divided up and the workers have been dispatched. In this case, the tallier knows that when the Workers list gets down to empty, the computation is finished.

2. Message from the manager that registers a worker with the tallier. The tallier adds this worker’s ID to the Workers list and waits for that worker to return his or her result.

3. Message from the worker indicating the worker’s ID and the result. The tallier removes the worker’s ID from the waiting pool and adds the result to the tally. When the waiting pool is empty and AssignFinished is true, it signals the end of the job and thus the tallier reports the final tally to the manager (solver).

There we go! Running the program on my work computer (QuadCore) gives me the correct result in less than 5 seconds. About 8 seconds for my laptop (which is a Core 2 Duo). Non of this is even remotely imaginable with the traditional approach.

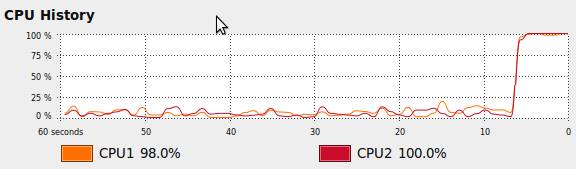

Also, as you may have guessed, all cores on the CPU are fully utilized.

CPU chart after

Programming in Erlang is fun!